The Fear of the New Coronavirus

Reading Time: 2-4 minutes

Monday morning, I took the plane from Vienna to go to the office in Milan. Arriving at the airport, I saw many Chinese people. Lots of them. I usually don’t notice this, because I have headphones on and I’m thinking about looking for the departure gate.

Some were wearing masks. Some perhaps weren’t exactly Chinese, maybe Japanese or Vietnamese. But I was very afraid. That they were sick. That they had the coronavirus.

I know it’s an unhealthy thought, I know. Probably, if the virus had taken hold in Spain, and I hadn’t been able to clearly recognize a Spaniard by their somatic features, I wouldn’t have been so afraid.

And instead I was. Because the potential carrier of this virus is a easily recognizable population: I recognize that there is also the misunderstanding linked to the fact that the person might not be Chinese but from a neighboring country (and therefore with very similar somatic features), but fear takes over.

Fear makes you think bad things. Like that you hate the Chinese because damn why the hell is it always them who trigger epidemics: and in 2003 with SARS, and now with the coronavirus.

And it’s always something new. Today you don’t die of smallpox because it’s extinct, theoretically not even of pneumonia because there is a cure. But of coronavirus today you die.

Just as people died of SARS.

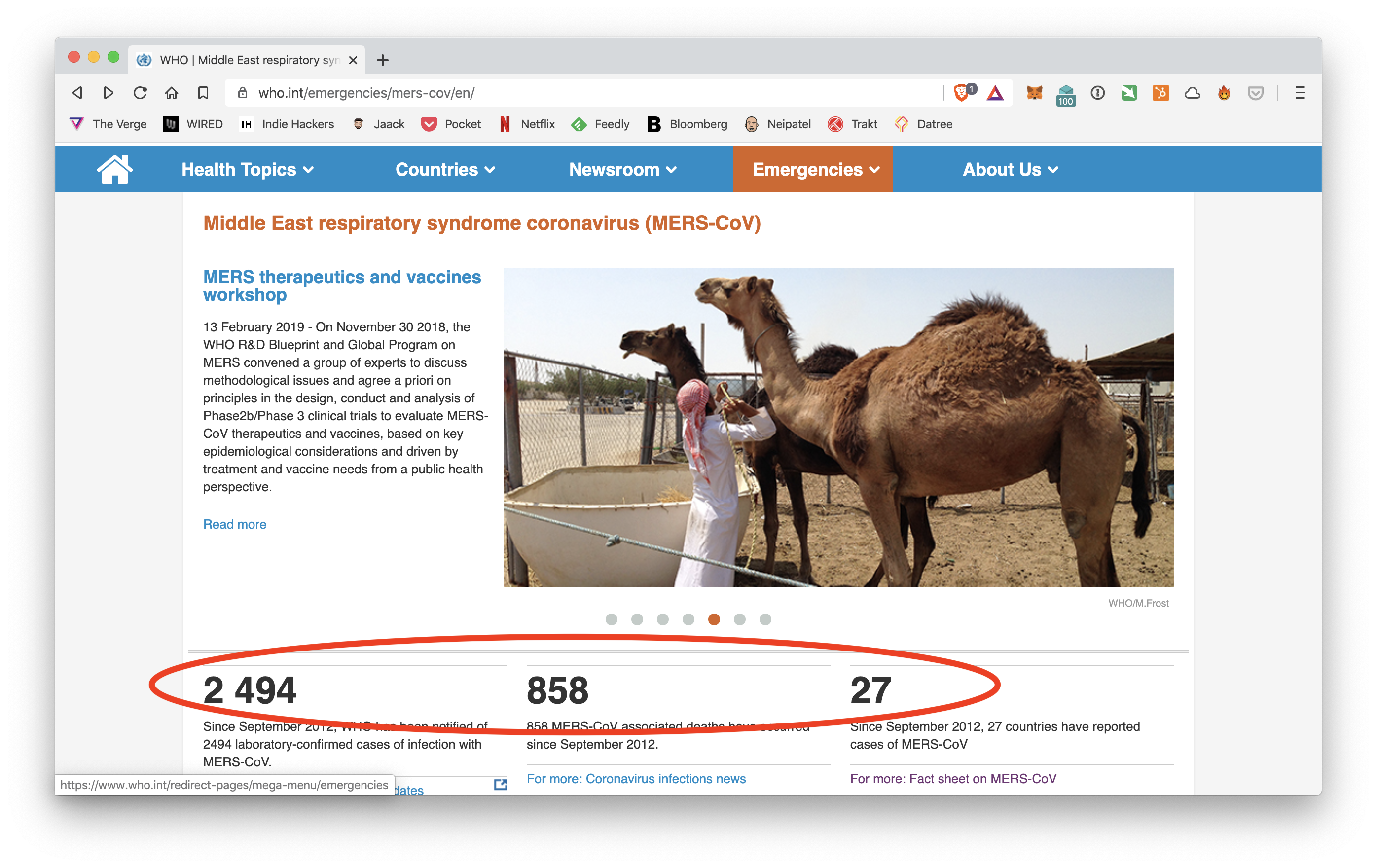

I went to see what happened with SARS and MERS (the latter is a virus that started in Saudi Arabia). With SARS the virus started from an animal, the civet cat, while with MERS from dromedaries. I studied the situation a bit on the official World Health Organization website and found some data that comforted me.

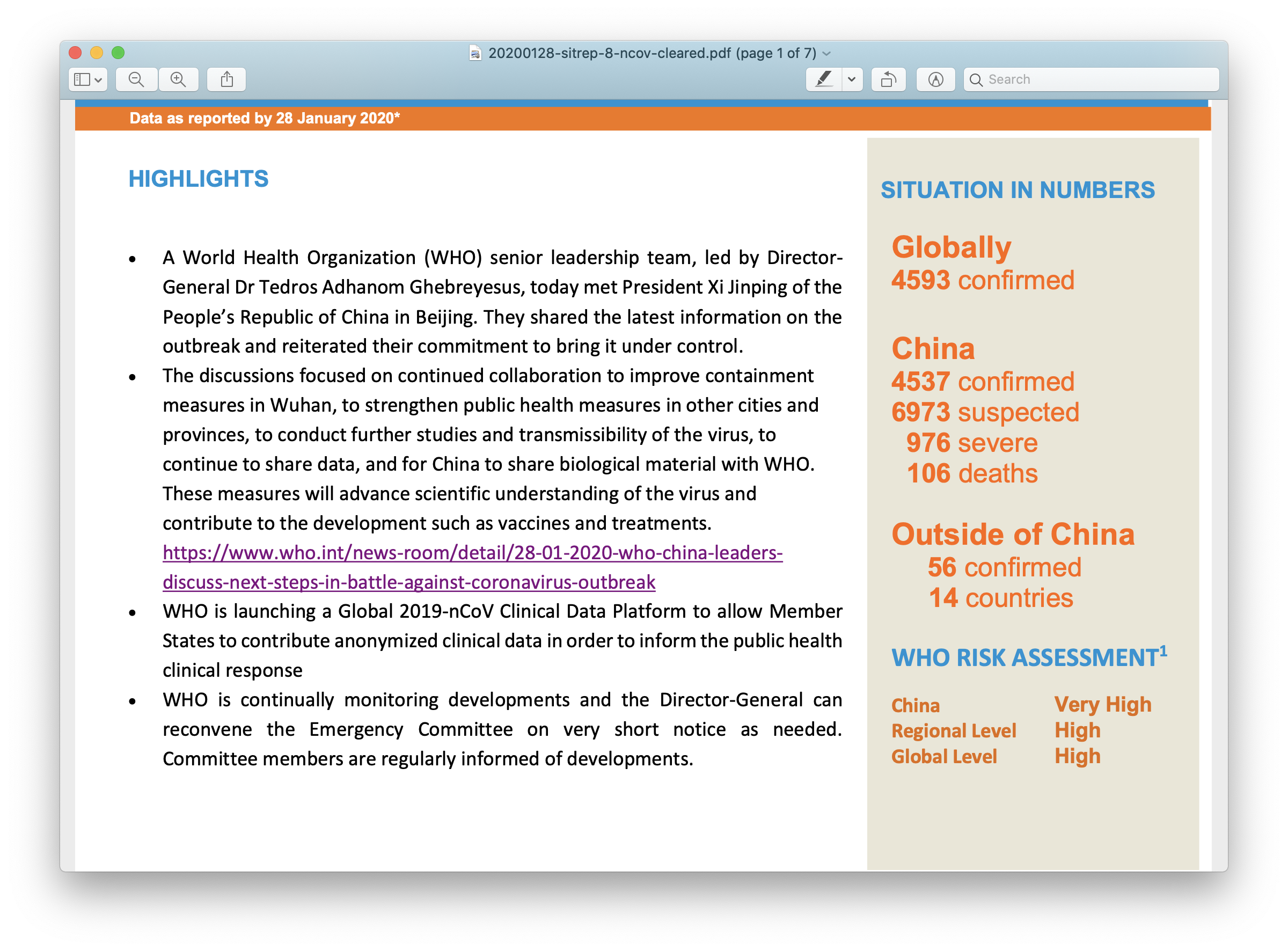

I understood, for example, that people still get sick with MERS today: they are few, certainly, and they are all in Saudi Arabia. A bit like when it is possible to catch malaria in some areas of Africa.

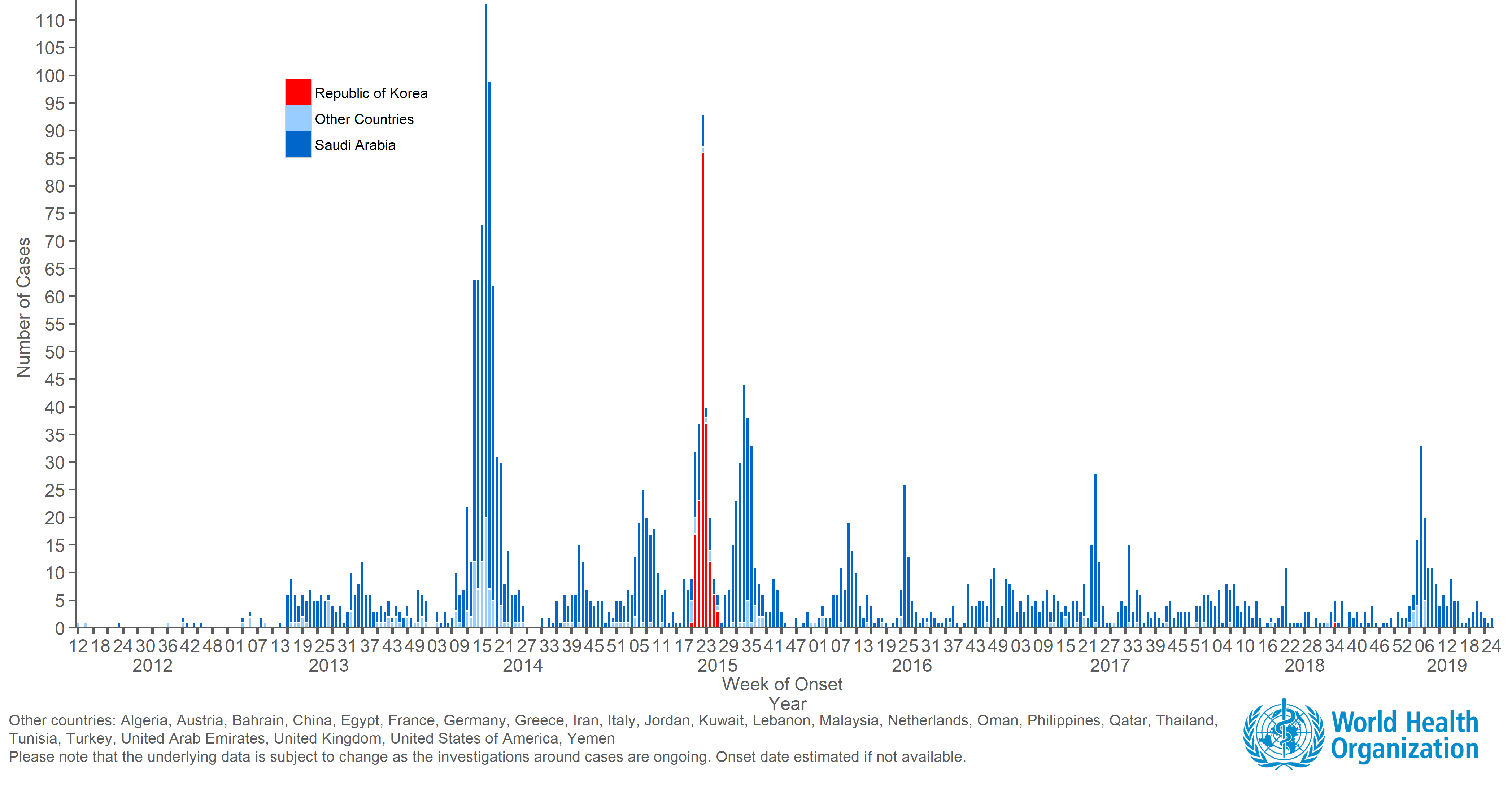

Then I discovered that SARS, MERS and nCov (the latter the name of the virus of this period) are all part of the strain of viruses called coronavirus. Then I went to study the entire expansion chain, so to speak, of these viruses. And I realized that SARS had a maximum of about 8,000 infected, almost 800 deaths in 29 countries.

I then went to see the victims of MERS, which did not start in China. And I realized that there were 3,000 cases.

Then a doubt came to me: why were there so many more infected by SARS than by MERS? Probably because in China there are just more people. So I went to Google and searched for data on the population of Saudi Arabia and China at the time of the two epidemics.

In 2002, there were about 1.28 billion people in China. In Saudi Arabia, in 2012-2013, there were 30 million people. OK, the comparison is merciless. But then I thought that, effectively, China is so big that one should not consider the whole country, but only the province where the epidemic started.

I summarize everything:

- In 2003, SARS first appeared in the province of Guangdong, which has about 100 million inhabitants (it’s the area bordering Hong Kong, to be clear) and had 8,000 cases and about 800 infected worldwide

- In 2012, when MERS appeared, in Saudi Arabia, the population basin was 30 million and about 2,500 people have been infected to date, with about 850 deaths

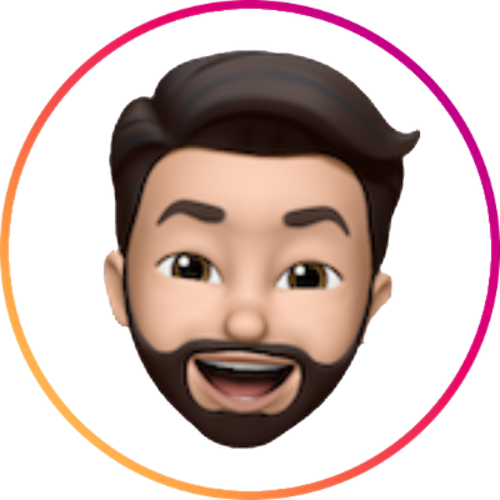

- Today, with the new coronavirus, the population living in the Hubei region, of 56 million people, has been isolated, and there are about 4,500 cases of infection with over 130 deaths

I am an aspiring engineer, so I like to do calculations and therefore find the percentage of infected compared to the reference population:

- SARS: 0.008%

- MERS: 0.008%

- nCov-2019: 0.008%

Surprisingly, the percentages are practically the same. It doesn’t seem like such an abnormal global epidemic, after all.

Maybe I’m not as afraid as before anymore. Luckily I looked into it.